News

Mourning The Loss of Shinzo Abe

The assassination of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe on July 8th 2022 will change economic-political-military dynamics in Japan and throughout the Asia Pacific. Abe’s brand of high-energy leadership will be sorely missed, particularly in the conduct of US-Japan relations. His absence will leave a serious void, perhaps diminishing the effectiveness of Japan’s role in Asia and the world.

Consolidator: Until 2012, politics in Japan had lacked gyroscopic stability. A parade of Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) leaders strolled into, and out of, the “kantei” (the Prime Minister’s office). Serving for only a year or two made it difficult for Prime Ministers to design national goals and to push through priority policy programs.

It’s not surprising, accordingly, that politics fell into a state of flux. None of the short-term Prime Ministers could summon the support necessary to address Japan’s chronic problems: decades of economic stagnation, asset deflation, a failure to harness the transformative wave of digital technology, and Japan’s peripheral position on the global stage—even as the world’s third biggest economy.

The state of disarray ended in 2012 when Shinzo Abe stepped back into the Prime Minister’s “kantei”. The merry-go-round came to a halt. The LDP’s machinery of governance was consolidated.

From 2012 – 20, Shinzo Abe managed to impose order and continuity, as he dedicated himself—heart, body, mind, and soul–to the historic challenge of reviving Japan’s sluggish economy and lifting Japan’s visibility, relevance, and voice in the word.

Abe drew up a sweeping vision for economic renewal. The plan called for the aggressive use of “Three Arrows”: opening the monetary spigots, turning on the fiscal hose, and fine-tuning corporate governance. Abe’s approach came to be known as “Abenomics”.

Although “Abenomics” has fallen short of achieving its lofty, long-term goals, the program has had the effect of recharging Japan’s run-down economy. It tripled the value of equity markets, lifted the employment rate from 56.5% (2012) to 60.7% (2019), ramped up international trade, and improved corporate balance sheets.

During his eight years in office, Shinzo Abe confronted the challenge of overhauling the country’s clunky political economy, creating a higher revving engine of governance and growth.

Primacy of Politics. Working closely with Deputy Prime Minister & Finance Minister Taro Aso, Shinzo Abe was able to harness the immense power of the Bank of Japan under the supervision of Governor Haruhiko Kuroda.

Abe also came up with a way to subordinate, quietly, the power of Japan’s entrenched bureaucracy–by exercising the Cabinet’s authority to approve job assignments and pivotal promotions within key ministries like the Ministry of Economy, Trade & Industry (METI) and the Ministry of Finance (MOF). The subordination of the bureaucracy represented a significant shift in the alignment of power within the central government.

Direct Descendants. It is noteworthy that Shinzo Abe hailed from Yamaguchi Prefecture in Southwestern Japan. Yamaguchi is the home of Abe’s forebearers—specifically, his grandfather, Nobusuke Kishi, and his great uncle, Eisaku Sato, both of whom had served as Prime Ministers in early postwar Japan.

The Edo era (1603-1867) was arguably the most unusual and formative chapter in Japanese history–two-and-a-half centuries of splendid isolation at a time of historic ferment in the West. Europe was going through the pangs of passage into modernity, driven by the Enlightenment (1685–1815), Industrialization (1760- 1840), and the revolutionary rise of democratic nation-states (1628 – 1800).

Yamaguchi Prefecture, which used to be called “Choshu”, spearheaded the movement to overthrow the Tokugawa “ancient regime”—in cahoots with two other feudal domains, “Tosa” (Koichi Prefecture today on the island of Shikoku); and “Satsuma” (Kagoshima Prefecture today on the island of Kyushu).

To consolidate the Prime Minister’s power from 2012 -20, Shinzo Abe leaned heavily on Taro Aso, who traces his lineage back to “Tosa” (Kochi) and “Satsuma” (Kagoshima). Aso happens to be the grandson of the founding “Godfather” of the LDP, Shigeru Yoshida (1946 – 47; and 1948 – 54), postwar Japan’s third longest-serving Prime Minister from Tosa. Aso is also the great-great grandson of Toshimichi Okubo (from Satsuma), a renowned samurai rebel, who played a pivotal role in the Meiji government.

From a historical perspective, the Abe-Aso team can be linked to the “Sat-Cho-To” (Satsuma-Choshu-Tosa) alliance of reform-minded “samurai” who brought about the Meiji Restoration (1867), the most consequential coup in Japanese history, ushering in Japan’s transition from an internationally isolated, feudal regime to a globally connected, constitutional state.

The thread of continuity is striking. The Abe-Aso team was, in a sense, the 21st century legacy of the 19th century “Sat-Cho-To” (Satsuma-Choshu-Tosa) insurrectionists and modern nation builders.

Global Trotter. Just as he consolidated the Prime Minister’s power base, Shinzo Abe has also elevated Japan’s global visibility, national prestige, and diplomatic leverage. He accomplished this by flying hundreds of thousands of miles, landing on every continent, and visiting scores of nation-states.

Debilitating Illness. Circling the globe can be utterly exhausting, even for physically fit leaders in the prime of their lives. Shinzo Abe was young but not in the best of physical health. From the age of 17, Abe became afflicted with a chronic illness–ulcerative colitis–a debilitating gastrointestinal disorder. The illness led to his resignation as Prime Minister in September 2007. And again in August 2020.

Medication helped to keep the colitis from flaring up, but it’s hard to imagine anyone with colitis traveling as tirelessly as Shinzo Abe.

Despite the exhausting demands of travel, Prime Minister Abe went about his daily duties with amazing zest. A bounce in his feet. Whenever I saw him, he always strode into rooms like an Olympic racewalker. Brimming with energy. Never once did I see him looking drowsy, sleepy, or listless.

Diplomatic Milestone: The Quad. On the foreign policy front, Prime Minister Abe has made a monumental contribution to regional peace, security, and prosperity by conceiving of, and helping to bring into existence, the Quad (the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue) involving Japan, India, Australia, and the United States. The Quad has taken shape in response to China’s rise as a potentially disruptive superpower. Abe saw the Quad as a versatile infrastructure to ensure a free and open Indo-Pacific region. It provides the multilateral framework for quadrilateral military exercises & training and the coordination of military strategy & policies.

Over the coming years, the Quad will be positioned to play a stabilizing role in addressing such regional threats as military conflicts and clashes, disruptions in sea and air travel, interruptions to trade and investment, containment of pandemics, energy shortages, and the cumulative ravages of climate change.

“Normal Nation, Japan”. A nationalist, deeply worried about Japanese security, Shinzo Abe assigned top priority to making the US-Japan Security Alliance—and US-Japan relations more broadly—as robust as possible.

He sought to loosen traditional constraints on Japan’s military power. What he desired, above all, was the revision of Article 9 of Japan’s postwar Constitution, which prohibits the use of military force outside of Japanese territory. No “normal” nation, he felt, should be forced to operate with their hands tied behind their backs. In a region—Asia–where security threats are mounting almost exponentially, Abe felt that the crippling handcuffs had to be loosened or removed altogether.

In 2015, against fierce opposition, the Abe administration managed to pass legislation, allowing Japanese military forces to be dispatched overseas to engage in combat operations in defense of allied nations. For Abe, this constituted a noteworthy but modest first step towards “normalization”.

In the end, Abe was not able to revise Japan’s constitution. Doing so would have required passage of a national referendum, which Abe and the LDP lacked sufficient leverage to push through. Constitutional revision will remain an issue with which future Prime Ministers may have to grapple.

Was Abe correct in assuming that the metastasizing threats to Japanese security—specifically, China’s military ascendancy, deepening Sino-American divide, and unremitting expansion of North Korea’s nuclear weapons capability —require a higher level of military preparedness?

The United States and NATO have rallied to Ukraine’s defense following Russia’s unprovoked invasion in 2022; but their support may have been powered by Ukraine’s courageous defense of its own homeland.

What about Japan? Will the United States be willing to rally to Japan’s defense if Japan lacks the national will and military clout to defend itself?

Trans-Pacific Trade. Another landmark breakthrough during Prime Minister Abe’s eight-years in office was Japan’s timely rescue of the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP), a multilateral trade and investment treaty, launched by the United States but cast aside, suddenly, by Donald Trump in 2017.

The TPP is the first time that a major multilateral treaty, left to wither and die on the vine by the United States, was kept alive and brought back to life by Japan. For this milestone achievement, Prime Minister Abe deserves fulsome praise.

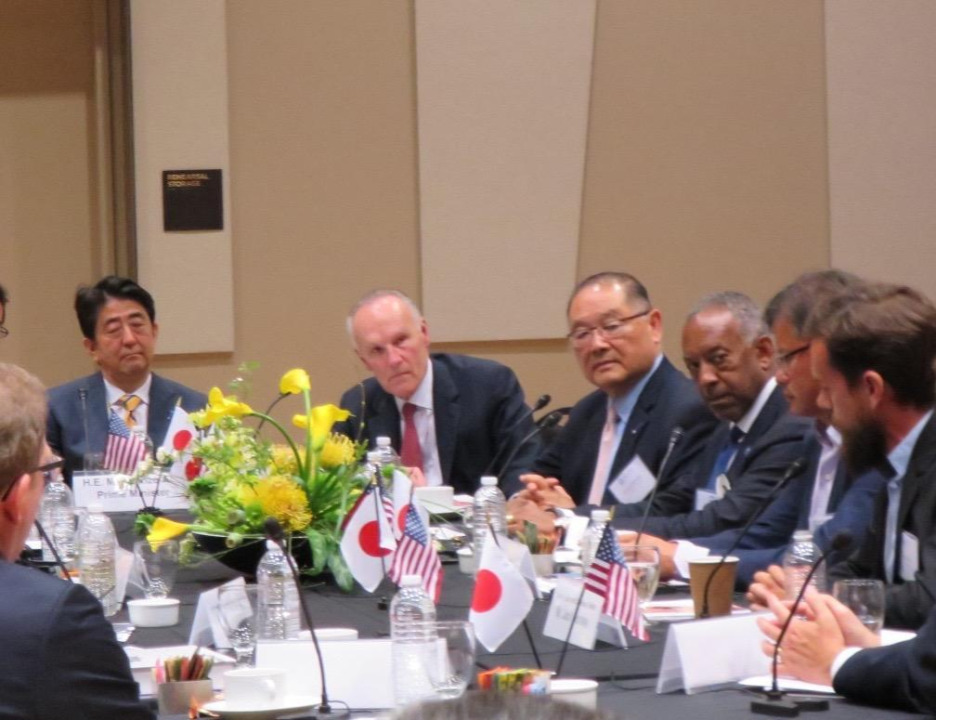

Silicon Valley. One destination where Prime Minister Abe made a stop on his whirlwind travels was Silicon Valley. April 30 – May 1, 2015.

The Silicon Valley Japan Platform (SVJP), a non-profit organization established in 2015 to deepen ties between Silicon Valley and Japan, invited Prime Minister Abe to visit the Mecca of Entrepreneurship and Innovation. Until 2015, no Japanese Head of State had ever stepped foot on the South Bay soil of Silicon Valley.

At Stanford University, at the head of a long conference table, Prime Minister Abe sat, surrounded by a galaxy of Silicon Valley pioneers, such as SVJP Advisor, Jerry Yang, co-founder and former CEO, Yahoo!, SVJP Advisor, John Thompson, Chairman at Microsoft; and Jack Dorsey, Co-founder and CEO, Twitter.

Abe sat in rapt attention as the lively discussion unfolded, assuming a “listen and learn” posture. One entrepreneur suggested that the Prime Minister consider establishing a Ministry of Digital Technology in Japan, just as Prime Minister Narendra Modi had done in India.

In 2021, the Suga Cabinet created the Japan Digital Agency designed to accelerate the digital transformation of the government.

In a moment of candor, another Silicon Valley icon observed that Japan simply had to let go of its obsessive fear of failure. In Silicon Valley, he said, repeated failures are commonplace. They are, indeed, a reassuring indicator of important lessons learned.

In an equally candid response, Abe said that future entrepreneurs in Japan might find solace—even inspiration—from Abe’s own “failures” during his first term in office, 2006-07. The words tumbled out of his mouth—with no hesitation or reluctance. Such self-criticism revealed the essence of Abe’s character: a man of candor and humility. What a disarming and poignant moment that was.

Abe’s Silicon Valley visit was game-changing. What it amounted to was a public proclamation—loudly and cogently communicated by Prime Minister Abe—that Japan is fully committed to adopting digital technology. Entrepreneurship and innovation will be the keys to unlocking the untapped potential of Japan’s economy.

Prime Minister Abe’s trip to Silicon Valley kicked-off what might be called a “Silicon Valley – Japan Boom”. Until 2015, it looked like China might come to exercise dominant control over venture investments, startup acquisitions, R&D, and manpower training and employment.

Since Abe’s visit, however, the tides have ebbed away from China. Japanese businesses have made substantial inroads into Silicon Valley. Yet, Japan is facing a steep uphill climb if it aspires to change the rigid, embedded structure of its hardware-based economy.

Shinzo Abe was among the early leaders to recognize the critical condition into which the Japanese economy had slipped—not to mention, the ominous clouds of uncertainty hovering over Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and the United States. Abe was a prophet, someone blessed with clairvoyance.

Several of the novel policy measures that Prime Minister Abe has initiated—including the greater integration of women in the labor force and stemming the tide of falling fertility and birth rates—have failed to heal the country’s debilitating ailments. But Abe deserves credit for breaking out of the mire of complacency and pushing forward vigorously to remedy Japan’s deep-seated ailments.

Nikkei Americans. Let me say, finally, how much I appreciated Prime Minister Abe’s support for, and feelings of affinity towards, “Nikkei Americans”. Not only was he an early proponent of the Silicon Valley Japan Platform (SVJP), but he was also an enthusiastic supporter of the U.S.-Japan Council (USJC).

Shinzo Abe routinely welcomed, and pro-actively sought, advice from iconic Japanese Americans like Secretary Norman Mineta and Senator Daniel Inouye, and from somewhat less renowned Japanese Americans, several of whom are active leaders of the USJC and the SVJP.

The US-Japan alliance is stronger and substantially more resilient, thanks to Prime Minister Abe ‘s cultivation of expansive ties with the Nikkei American community.

Today, Japan commands the global respect that Shinzo Abe had worked so assiduously to cultivate.

Like so many others around the world today, I deeply mourn his premature passing.

Shinzo Abe will be remembered. He will be missed.

His legacy will endure.

Daniel I. Okimoto